Woven in Light: The Shendyt, Kalasiris, and Sacred Dress of Ancient Egypt ✨

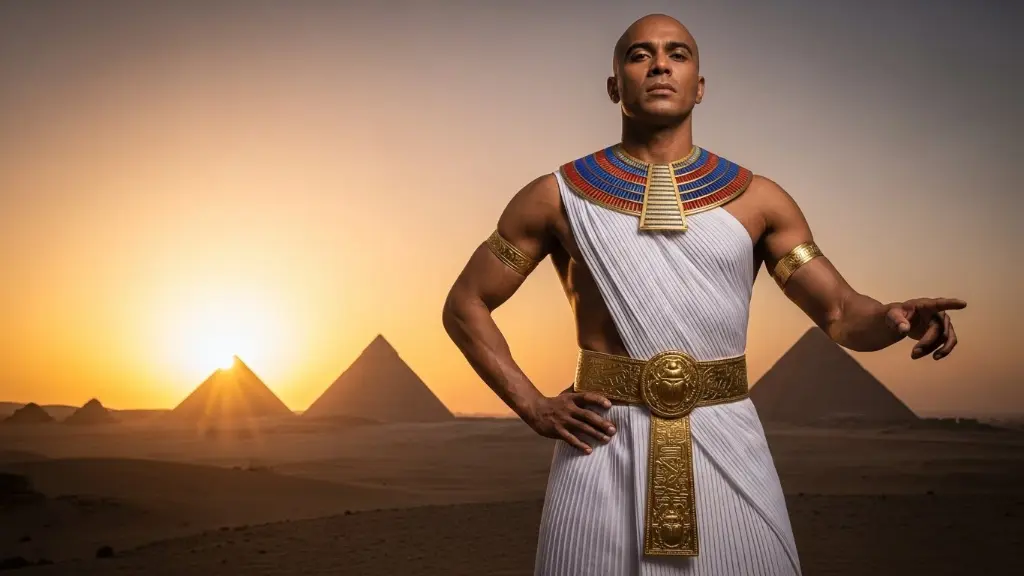

Step from the blinding desert sun into the cool, silent darkness of an ancient tomb. On the walls, painted figures live for eternity. A powerful pharaoh, muscles taut, smites his enemies. A graceful noblewoman offers lotus flowers to the gods. A farmer harvests golden fields of grain. They are frozen in time, yet they speak to us through a silent, elegant language: the language of their clothing.

Ancient Egyptian dress was far more than simple protection from the heat. It was a sophisticated system of order, status, and sacred symbolism, as integral to their civilization as the pyramids themselves. Each fold of linen, each gleaming piece of jewelry, and each stroke of kohl around the eye was a deliberate statement about one’s place in the cosmos.

This article will unravel the threads of the ancient Egyptian wardrobe. We will explore the iconic Shendyt of the pharaoh, the elegant Kalasiris of the noblewoman, and the breathtaking array of symbolic accessories that transformed simple garments into wearable prayers. Prepare to discover a world where clothing was not just worn, but was a living expression of divine order, social hierarchy, and the eternal journey of the soul.

🌱 The Fabric of a Civilization: The Miracle of Linen

Before we can understand the clothes, we must understand the cloth. For the ancient Egyptians, one material reigned supreme, a gift from the fertile black earth of the Nile Valley: linen.

See also Threads of the Nile: A Regional Guide to Egyptian Cultural Dress 🇪🇬

Threads of the Nile: A Regional Guide to Egyptian Cultural Dress 🇪🇬Linen, made from the fibers of the flax plant, was the perfect fabric for a life lived under the powerful Egyptian sun. It was lightweight, breathable, and wicked moisture away from the body, providing natural air conditioning. But its significance went far beyond the practical.

- The Color of Purity: The vast majority of Egyptian clothing was white. White linen was a symbol of purity, light, and cleanliness—concepts central to the Egyptian worldview, which prized order (Ma’at) over chaos. While other colors were used in decoration, the base was almost always the pristine white of bleached linen.

- A Labor of Love: Creating linen was a laborious process. Flax was harvested, soaked (retted) to break down the woody stem, beaten to separate the fibers, and then spun into thread by hand. The thread was then woven on horizontal looms. The quality could range from coarse, rough cloth for a laborer’s loincloth to a whisper-thin, almost transparent royal linen known as “woven air.”

- Aversion to Wool 🐑: Wool was known, but it was generally considered impure. It was rarely worn by priests or for religious ceremonies and was forbidden in temples and tombs. Herodotus noted that no Egyptian would be buried in a woolen garment. Clothing was for both the living and the dead, and only the purest material would suffice for eternity.

👑 The Shendyt: A Garment of Masculine Power

The most iconic and enduring garment for the Egyptian man was the Shendyt, a wrap-around kilt or loincloth. Its elegant simplicity is deceptive; its form and fabric were a clear indicator of the wearer’s status and role.

The Practical Kilt of the Common Man

For the farmer, the fisherman, the soldier, and the craftsman, the shendyt was pure practicality.

- It was a short, simple wrap of coarse linen, providing maximum freedom of movement for physical labor.

- It offered protection from the sun while keeping the wearer cool.

- It required a minimal amount of precious fabric.

In tomb paintings, we see legions of laborers, all clad in this basic, functional kilt, a uniform of the working class.

See also Traditional Clothing of Egypt: A Timeless Blend of Heritage and Culture

Traditional Clothing of Egypt: A Timeless Blend of Heritage and CultureThe Pleated Proclamation of the Pharaoh

For the pharaoh and the nobility, the shendyt was transformed from a tool of labor into a symbol of supreme power and leisure.

- Immaculate Pleating: The shendyt of a high-status man was longer and made of the finest linen. Most importantly, it was meticulously pleated. These tiny, precise pleats were set using moisture and weights, a time-consuming process that would have to be redone after every washing. The crisp, elaborate pleating was an immediate sign that the wearer did no manual labor whatsoever.

- The Stiffened Front Panel: Often, the royal shendyt featured a stiff, starched front panel, sometimes shaped like a triangle or trapezoid, further enhancing its sculptural, non-functional quality.

- The Bull’s Tail: From the earliest dynasties, the pharaoh was often depicted wearing a ceremonial bull’s tail attached to the back of his shendyt. This was a direct and powerful symbol of his strength, procreative power, and divine might, linking him to the potent symbolism of the sacred bull.

From the Narmer Palette (c. 3100 BCE) to the golden shrines of Tutankhamun, the pharaoh is almost always shown in this iconic garment—a symbol of his eternal, masculine authority.

💃 The Kalasiris: An Icon of Feminine Grace

The primary garment for the Egyptian woman was a beautifully simple sheath dress, which the ancient Greeks later called the Kalasiris. (The original Egyptian name is uncertain). Its form celebrated the female body while maintaining a sense of divine, column-like elegance.

A Column of White

In its most common form, the Kalasiris was a long, narrow sheath that extended from just below the breasts to the ankles. It was held up by two straps that tied behind the neck or attached over the shoulders.

- The Ideal Silhouette: This form created a tall, slender, columnar silhouette that echoed the architecture of their temples. It was often depicted as being incredibly tight-fitting in art, though in reality, it likely had enough room for movement. The artistic convention was to reveal the shape of the body beneath the cloth, emphasizing grace and fertility.

- A Canvas for Accessories: The simple, white form of the Kalasiris was the perfect neutral canvas for the Egyptians’ true passion: elaborate, colorful, and deeply symbolic accessories. The dress was the foundation; the jewelry and collar were the main event.

New Kingdom Innovations

During the New Kingdom (c. 1550-1070 BCE), a period of immense wealth and foreign contact, fashion became more elaborate.

- A second, more voluminous robe was often worn over the traditional Kalasiris. This outer robe could be made of intricately pleated, transparent linen, creating a layered, ethereal effect.

- The sleeves became a focus, with wide, flowing, pleated sleeves adding drama and a sense of luxury.

- Bead-net dresses, intricate nets of colorful faience beads, were sometimes worn over the linen sheath. A beautiful example was found in a 5th Dynasty tomb, proving this was not just an artistic fantasy.

The Kalasiris, in all its forms, represented the Egyptian ideal of femininity: graceful, serene, and elegant.

✨ A Woven Hierarchy: Clothing as a Social Ladder

In the strictly ordered society of ancient Egypt, clothing was an instant and unmistakable social signal. You were what you wore.

| Social Class | Garment Style & Materials | Symbolism & Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Peasants & Laborers | Short, simple loincloths or shendyts of coarse, undyed linen. Children often went naked. | Practicality. Designed for work and the heat. Minimal fabric use. |

| Scribes & Officials | Longer, finer linen kilts or robes. Pleated details begin to appear. | Leisure & Status. Longer garments indicate a non-laboring role. Finer linen shows wealth. |

| Nobility | Very fine, pleated linen robes. Sheer, almost transparent fabrics. Layered garments. | Elite Status & Luxury. “Woven air” linen was extremely expensive. Complex pleating required servants. |

| Priests | Wore specific ceremonial garments, often a leopard skin over their linen robes. | Sacred Authority. The leopard skin symbolized their power over the forces of chaos and their role as intermediaries. |

| Pharaoh & Royalty | The finest “royal linen,” elaborate pleating, exclusive symbols like the Nemes headdress and bull’s tail. | Divinity & Supreme Power. Their clothing set them apart from all mortals, marking them as gods on Earth. |

💎 The Language of Accessories: More Than Just Jewelry

The true splendor of Egyptian dress lay in its accessories. For the Egyptians, jewelry and adornment were not frivolous extras; they were essential pieces of spiritual technology, imbued with protective power and divine meaning.

The Usekh Collar: The Sun’s Embrace ☀️

The most iconic piece of Egyptian jewelry is the Usekh or Wesekh, a broad, elaborate collar that covered the shoulders and chest.

- Construction: It was made of multiple rows of colorful beads made from faience, glass, and semi-precious stones like lapis lazuli, carnelian, and turquoise, all strung together and ending in a decorative clasp.

- Symbolism: The Usekh’s shape is believed to represent the rays of the sun god, Ra, embracing the wearer. It was a symbol of protection and divine favor. Its weight on the shoulders would have been a constant, physical reminder of one’s connection to the gods.

Wigs and Headwear: The Crowning Glory 👑

Both men and women of the upper classes shaved their heads for hygiene and to combat lice. They then wore elaborate wigs made of human hair, horsehair, or plant fibers.

- Practicality and Status: Wigs protected the scalp from the sun, but more importantly, they were a major status symbol. A large, complex wig made of real human hair was incredibly expensive.

- The Nemes Headdress: Reserved exclusively for the pharaoh, the Nemes was a striped linen headcloth that covered the whole head and draped down behind the ears and over the shoulders. The golden mask of Tutankhamun, with its iconic blue-and-gold Nemes, has made it the ultimate symbol of pharaonic power.

- The Vulture Crown: Worn by queens and goddesses, this crown featured the head and wings of a vulture, symbolizing the protection of the vulture goddess Nekhbet.

Kohl and Cosmetics: The Gaze of the Gods 👁️

The famous “cat-eye” look of the ancient Egyptians was not just about beauty. The black kohl they used to line their eyes was made from ground galena (a lead sulfide).

- Practical Use: The dark liner helped to reduce the blinding glare of the desert sun.

- Magical Protection: More importantly, it was believed to have magical protective properties. By outlining the eye, they were invoking the power of the Eye of Horus (the Udjat), a potent symbol of healing, protection, and wholeness. The green eyeshadow they often wore, made from malachite, was also associated with fertility and rebirth.

Amulets and Sacred Jewelry: Wearable Prayers 🙏

Jewelry was rarely just decorative. Most pieces incorporated powerful amulets designed to protect the wearer in both this life and the next.

- The Ankh ☥: The symbol of “life,” it was one of the most powerful and common amulets, worn to grant a long life and a healthy afterlife.

- The Scarab Beetle (Khepri) 🐞: The scarab beetle, which rolls a ball of dung from which its young emerge, was a potent symbol of creation and rebirth. It was linked to the sun god Khepri, who was believed to roll the sun across the sky each day. Scarab amulets were worn for renewal and were famously placed over the heart of a mummy to ensure its rebirth.

- The Djed Pillar: A symbol representing the backbone of the god Osiris, it stood for stability, endurance, and resurrection.

⚰️ Clothing for Eternity: The Wardrobe of the Afterlife

The Egyptians believed the afterlife was a real, physical place where their soul (Ka) would need all the comforts of earthly life. This included a full wardrobe. Tombs were filled with chests of clothing, and the tomb of Tutankhamun famously contained hundreds of garments, including tunics, kilts, loincloths, and even decorated leather gloves.

The final and most important garment of all was the mummy wrapping. The body was painstakingly wrapped in hundreds of yards of the finest linen, with sacred amulets tucked between the layers. This was not just preservation; it was a sacred act of clothing the deceased for their final journey, transforming them into a divine being, an Osiris, ready to be reborn into the eternal light.

Conclusion: A Legacy Woven in Time

Ancient Egyptian clothing was a brilliant, unified system that expressed the very core of their worldview. It was practical for the climate, yet it was also a rigid enforcer of social hierarchy and a profound expression of spiritual belief. The simple elegance of the Shendyt and Kalasiris provided the canvas, but it was the layers of pleats, the gleam of the Usekh collar, and the protective power of the Ankh and the Scarab that completed the picture.

This was a civilization that saw the divine in every aspect of life, and they dressed accordingly. Their clothing was a constant, visible prayer—a celebration of order, a shield against chaos, and a hopeful preparation for an eternal life lived in the brilliant, unending light of the gods. The threads have long since turned to dust, but the stories they tell are as timeless as the pyramids themselves.

Which piece of Ancient Egyptian adornment do you find most fascinating? The protective Eye of Horus kohl or the sun-embracing Usekh collar? Share your thoughts in the comments below! 👇

❓ Frequently Asked Questions about Ancient Egyptian Clothing

Q1: Did Ancient Egyptians wear underwear?

A: Yes! Both men and women wore a simple triangular loincloth made of linen, similar to a diaper, as an undergarment. Several well-preserved examples were found in Tutankhamun’s tomb.

Q2: Did they wear shoes?

A: For the most part, Egyptians of all classes went barefoot, especially indoors. However, they did have simple sandals made from woven papyrus or palm leaves for rough terrain or important occasions. The pharaoh often had incredibly ornate sandals, sometimes decorated with images of his enemies on the soles so he would symbolically crush them with every step.

Q3: Why was most of their clothing white?

A: There were two main reasons. Practical: White reflects the sun’s heat, making it the most comfortable color for a hot climate. Symbolic: White was seen as the color of purity and light, which were central concepts in their religion (Ma’at). It was also difficult to dye linen effectively with many of the natural dyes available.

Q4: How do we know so much about their clothing?

A: Our knowledge comes from three incredible sources: Art (tomb paintings and temple reliefs show countless details of what people wore), Archaeology (actual garments have been preserved by the dry desert climate, most famously in Tutankhamun’s tomb), and Texts (hieroglyphic texts sometimes describe clothing or list them in inventories).