A Journey into the World of Ancestral Clothing

Have you ever held a faded, sepia-toned photograph of a great-grandparent? As you trace the unfamiliar lines of their face, your eyes inevitably drift to their clothing: the stiff collar, the hand-stitched lace, the sturdy wool of a farmer’s coat. In those threads, a silent story is waiting to be told. The garments of our ancestors were far more than just fabric. They were their armor, their language, their prayers, and their legacy.

This article embarks on a journey back in time, unraveling the rich and complex world of ancestral clothing. We will explore how the first garments were humanity’s most crucial technology for survival. We will decode the intricate language of dress that announced identity, status, and tribe. Finally, we will touch the sacred threads that connected our ancestors to their gods and discover how their clothing still whispers to us today, in our family histories, our cultural celebrations, and even our modern fashion.

Prepare to look at clothing not as a disposable trend, but as a deep, powerful, and essential part of the human story—a story that is woven into your own DNA.

❄️ The First Garment: A Shield Against the World

Long before clothing became a statement, it was a necessity. It was humanity’s first fortress—a supple armor against biting winds, scorching sun, relentless rain, and the hostile wilderness. The story of ancestral clothing begins not with fashion, but with the primal, urgent need to survive.

See also Cultural Diversity in Arab Countries

Cultural Diversity in Arab CountriesFrom Hide to Home: The Paleolithic Wardrobe

For tens of thousands of years, our earliest ancestors were masters of adaptation. Their wardrobe was a direct product of their environment and their prey.

- The Warmth of the Hunt: In the icy landscapes of Paleolithic Europe and Asia, the primary materials were animal hides and furs. The woolly mammoth, the bison, and the cave bear provided not just food, but thick, insulating pelts that became humanity’s first blankets and cloaks.

- The Birth of the Needle: The invention of the bone needle, some 60,000 years ago, was a revolutionary leap in clothing technology. This simple, elegant tool allowed our ancestors to move beyond simply draping hides. They could now cut, shape, and stitch pieces together, creating fitted trousers, tunics, and parkas. This was the birth of tailoring, a skill born from the need to conserve heat and allow for greater mobility while hunting.

- Beyond Fur: In warmer climates, survival meant protection from the sun and insects. Large leaves, beaten tree bark (like the tapa cloth of the Pacific Islands), and woven grasses served as humanity’s first breathable, lightweight garments.

These early clothes were not just practical; they were imbued with the spirit of the animal from which they came. To wear the pelt of a great bear was to perhaps invoke its strength; to wear the hide of a swift deer was to honor its grace. From the very beginning, clothing was both a physical shield and a spiritual connection.

The Neolithic Weaving Revolution 🌱

The dawn of agriculture, around 10,000 BCE, changed everything, including our closets. As humans settled down, they domesticated not only plants and animals for food but also for fiber. This sparked the second great clothing revolution: weaving.

- Linen: In the Fertile Crescent and Egypt, humans learned to cultivate the flax plant. They painstakingly harvested its stalks, retted them in water, and spun the fine fibers into linen thread—a cool, absorbent, and durable material perfect for hot climates. Ancient Egyptian mummies were famously wrapped in hundreds of yards of fine linen, preserving them for eternity.

- Wool: In the highlands of Eurasia, the domestication of sheep provided a new source of miraculous fiber: wool. Unlike hides, wool was renewable. It could be shorn, spun, and woven into warm, water-resistant textiles. The invention of the loom allowed for the creation of large, complex pieces of cloth, paving the way for the development of draped garments like the Greek chiton and the Roman toga.

This shift from hide to woven textile was monumental. It allowed for dyeing, patterning, and the creation of clothing that was less about the shape of an animal and more about the imagination of the human weaver.

See also Day of the Dead: A Vibrant Celebration of Life, Love, and Remembrance 🎊💀🌸

Day of the Dead: A Vibrant Celebration of Life, Love, and Remembrance 🎊💀🌸

👑 A Woven Language: Dress as Identity and Status

As societies grew more complex, clothing evolved from a simple shield into a sophisticated visual language. What an ancestor wore could instantly tell you everything you needed to know about them: their tribe, their wealth, their profession, their marital status, and their place in the rigid hierarchy of their world.

A Tapestry of Tribe and Place 🗺️

For much of human history, you wore your home. Your clothing was a map of your origins, woven from local materials and dyed with local plants, instantly identifying you as a member of a specific tribe or region.

- The Scottish Tartan: Perhaps the most famous example, the tartan of the Scottish Highlands was a declaration of clan identity. Each clan had its own unique pattern, or sett, woven in specific colors derived from the local vegetation. To see a man’s tartan was to know his allegiance—a Campbell, a MacDonald, a MacGregor. It was a uniform of kinship.

- The Maasai Shuka: The vibrant red cloth worn by the Maasai people of Kenya and Tanzania is instantly recognizable. The red is said to represent bravery and the blood of the cattle that are central to their culture, while the pattern can distinguish different age-sets and groups. It is a bold declaration of cultural identity against the vast landscape of the Great Rift Valley.

The Hierarchy of the Hemline 🏛️

In stratified societies, clothing was a primary tool for enforcing social order. Sumptuary laws were common across the ancient and medieval worlds—strict regulations that dictated what a person could or could not wear based on their social rank.

- The Roman Toga: In Ancient Rome, not all togas were created equal. The simple, off-white toga virilis was worn by the common male citizen. The toga praetexta, with its woven purple border, was reserved for magistrates and high priests. An aspiring politician wore a brilliantly whitened toga candida (the origin of our word “candidate”), while a mourner wore a dark toga pulla. The toga was a citizen’s uniform, its color and quality a constant, public reminder of his place.

- The Power of Purple: For centuries, the color purple was the ultimate status symbol. Tyrian purple, a dye laboriously extracted from thousands of sea snails, was astronomically expensive. Its use was restricted to emperors, senators, and royalty. To wear purple was not just to be wealthy; it was to claim a connection to divinity and absolute power.

Rites of Passage: Dressing for Life’s Great Moments 👰♀️🤵♂️

Ancestral clothing also marked the turning points in a person’s life, guiding them from one stage to the next.

- Coming of Age: A boy receiving his first Tuareg Tagelmust in the Sahara, or a young woman in a Native American tribe receiving the dress she will wear for her womanhood ceremony, is given more than a garment. She is given a new identity, a new set of responsibilities, and a new place in her community.

- Marriage: The white wedding dress is a relatively modern Western tradition, popularized by Queen Victoria in 1840. For much of history, a bride simply wore her finest dress, which was often red in many cultures (like China and India) to symbolize luck, joy, and fertility. The garment itself was a focal point of the transfer of wealth and the joining of families.

- Mourning: The black attire of Western mourning is another Victorian convention. In many ancient societies, including Rome and parts of Asia, the color of mourning was white, symbolizing the soul’s purity and its journey to the afterlife. The clothing of grief was a social signal, giving the wearer space to mourn and the community a way to show respect.

🙏 Sacred Threads: Clothing as a Spiritual Connection

For our ancestors, the physical and spiritual worlds were not separate. The world was alive with gods, spirits, and unseen forces, and clothing was a critical tool for navigating this enchanted reality. It could protect, empower, and serve as a bridge to the divine.

Colors of the Cosmos 🎨

Colors were rarely just decorative; they were imbued with potent spiritual meaning.

- White: Universally associated with purity, light, and the sacred. Worn by priests in ancient Egypt, by Roman Vestal Virgins, and by pilgrims of many faiths.

- Red: The color of blood, and therefore of life, vitality, passion, and power. Red ochre was one of the first pigments used by humans to adorn their bodies and graves.

- Blue: The color of the sky and the heavens, representing divinity, truth, and tranquility. The Virgin Mary is often depicted in blue, and the robes of many ancient deities were described as sky-blue.

- Saffron: In Hinduism and Buddhism, this brilliant yellow-orange color, worn by monks and holy men, symbolizes renunciation, sacrifice, and the quest for enlightenment. 🔥

Patterns of Protection and Power 🧿

Patterns were not just for beauty; they were often powerful symbols, amulets woven directly into the cloth to shield the wearer from harm.

- The Evil Eye: The belief in the “evil eye”—a malevolent glare that can cause misfortune—is ancient and widespread. In the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of Europe, the symbol of the Nazar (a blue and white eye) or the Hamsa (a stylized hand) was incorporated into clothing and jewelry to repel this negative energy.

- Knotwork: In Celtic and Norse cultures, intricate, unending knot patterns symbolized eternity, the interconnectedness of life, and spiritual protection. These knots, with no beginning and no end, were believed to trap evil spirits.

- Sacred Geometry: From the mandalas of the East to the diamond patterns of Berber weavers, geometric shapes were often representations of the cosmic order, balance, and harmony. To wear them was to align oneself with that divine order.

Garments of the Gods ✨

In nearly every culture, those who communicated with the divine—priests, shamans, and ceremonial leaders—wore special garments. This ceremonial regalia set them apart and was believed to help them cross the threshold between the human and spirit worlds.

A Siberian shaman might wear a coat hung with metal charms and ribbons representing the spirits he commanded. A Catholic priest dons vestments whose colors align with the liturgical season. A Native American dancer wears regalia made of eagle feathers to carry prayers to the Creator. These are not mere clothes; they are tools of transformation.

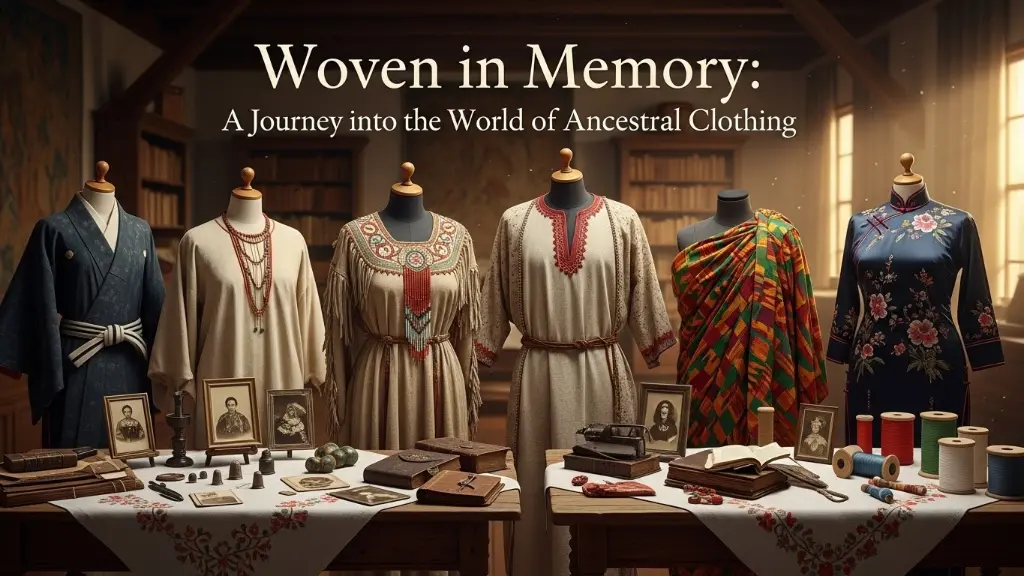

🔗 The Loom of Legacy: How We Connect with Ancestral Clothing Today

The world of our ancestors may seem distant, but their threads are still woven into the fabric of our modern lives. In an age of fast fashion and globalized trends, there is a growing, deep-seated human need to connect with something more authentic, something that tells our own unique story.

The Rise of Genetic Genealogy and Cultural Curiosity 🧬

The explosion in DNA testing services like AncestryDNA and 23andMe has ignited a powerful curiosity about our roots. Discovering you have “30% Scottish” or “15% Nigerian” heritage often sparks a desire to connect with that culture. This frequently manifests in a desire to explore its traditional dress. Suddenly, the Scottish kilt, the Norwegian bunad, or the West African dashiki becomes more than just an interesting garment; it becomes a piece of one’s own rediscovered story.

Historical Reenactment and Living History 📜

For some, the connection is more hands-on. Historical reenactors and living history enthusiasts dedicate themselves to recreating the clothing of the past with painstaking accuracy. They learn to spin wool, weave on traditional looms, dye with natural plants, and sew by hand. This is an act of deep reverence. As one reenactor might put it, “When I wear these clothes, made the old way, I’m not just playing a part. I’m trying to understand my ancestors’ world from the inside out.”

The Echo in Modern Fashion 👠

Look closely at a modern runway, and you will see the ghosts of ancestral clothing everywhere.

- The flowing lines of the Japanese kimono inspire modern robes and jackets.

- The comfortable elegance of the North African kaftan has become a staple of resort and lounge wear.

- The intricate draping of the Indian sari influences high-fashion evening gowns.

Designers continually draw from this vast global wardrobe, seeking the timeless beauty, functionality, and storytelling power of traditional dress. This raises important questions about cultural appreciation vs. appropriation—a reminder that these garments have deep meaning and should be approached with respect, not simply taken as a trend.

Your Own Woven Story

The clothing of our ancestors was their primary interface with the world. It was their first shelter, their most immediate form of communication, and their most personal connection to the sacred. It was a language of wool and linen, of hide and silk, that spoke of power, piety, love, and loss.

Every stitch told a story. Every color held a prayer. Every fold contained a memory.

Today, as you choose your own clothes, take a moment to think about the threads of your own history. The garments you wear now will be the “ancestral clothing” of your descendants. What story will they tell about you, about your life, about the world you lived in? In a very real way, the loom of legacy never stops weaving, and you are a part of its unending pattern.

What stories does your family have about ancestral clothing? A grandmother’s wedding dress? A grandfather’s military uniform? Share your own “threads of time” in the comments below! 👇 We’d love to hear them.

❓ Frequently Asked Questions about Ancestral Clothing

Q1: How can I learn about the clothing my specific ancestors wore?

A: Your research can be a fascinating journey! Start with family photos and documents. Visit local history museums and archives where your ancestors lived. Genealogical societies often have resources on historical dress. Books on the history of costume and specific cultural textiles are also invaluable.

Q2: What is the difference between cultural appreciation and cultural appropriation?

A: This is a crucial distinction. Appreciation is learning about, honoring, and respecting another culture. It might involve buying a garment directly from an artisan of that culture or studying its history. Appropriation is taking elements from a marginalized culture without understanding or respecting their significance, often for personal profit or as a costume. The key is context, respect, and who holds the power.

Q3: Why was clothing so expensive in the past?

A: Before the Industrial Revolution, every step of making cloth was done by hand. From growing the flax or raising the sheep, to harvesting, processing, spinning the fibers into thread, weaving the thread into cloth, and finally sewing the cloth into a garment—it represented hundreds of hours of labor. A single tunic could be a significant portion of a person’s annual wealth.

Q4: Are there people who still make clothing in traditional, ancestral ways?

A: Absolutely! Around the world, there are thousands of dedicated artisans, cultural bearers, and craftspeople keeping these traditions alive. From Harris Tweed weavers in Scotland to indigo dyers in Japan and Navajo weavers in the American Southwest, these individuals are living libraries of ancestral knowledge. Supporting their work is one of the best ways to ensure these sacred threads are not lost.